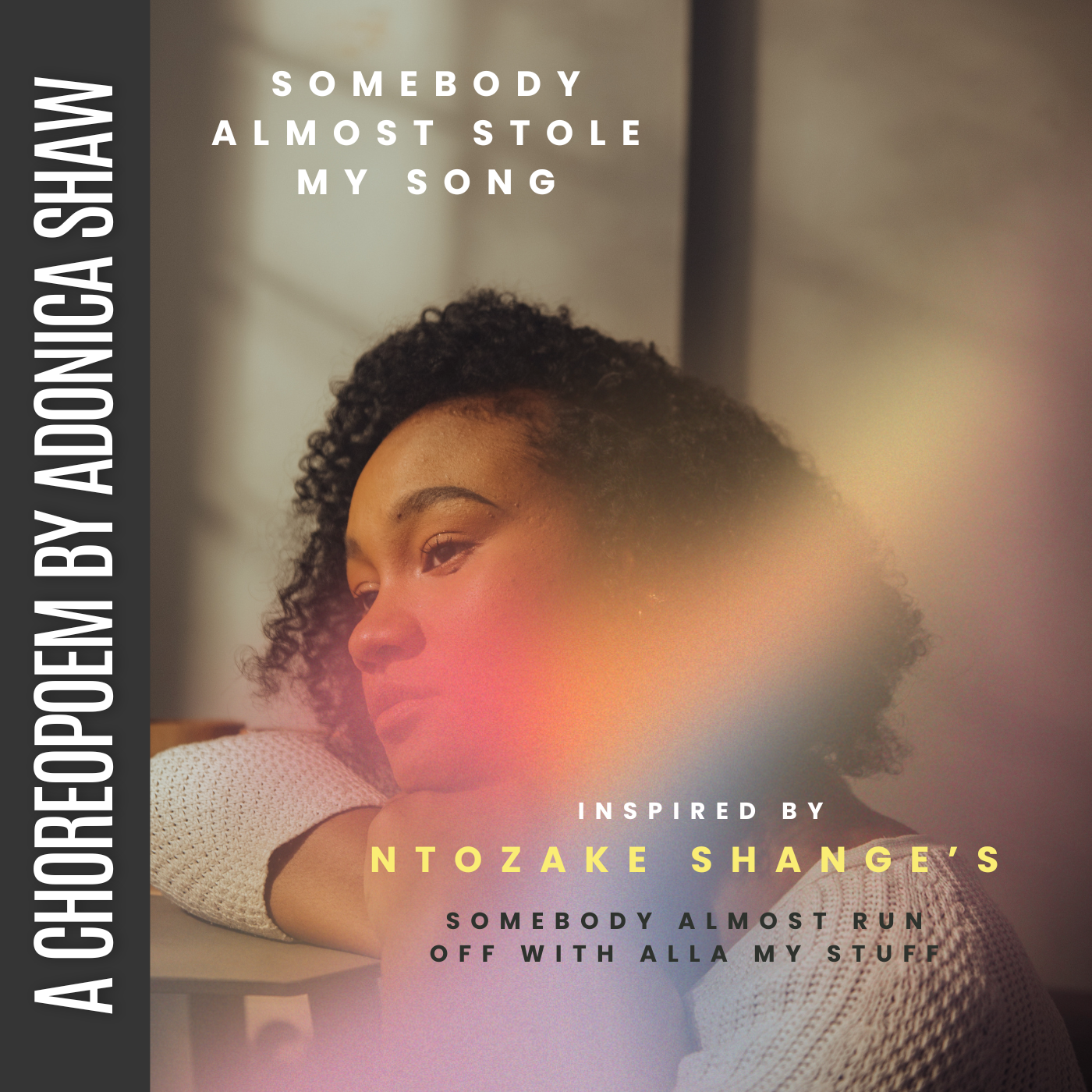

Somebody Almost Stole My Song: A Response to Ntozake Shange’s Legacy

Inspired by Ntozake Shange’s groundbreaking choreopoem for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, Adonica Shaw’s “Somebody Almost Stole My Song” continues the legacy of Shange’s iconic monologue “Somebody Almost Walked off Wid Alla My Stuff.”

Shaw’s piece honors women reclaiming their bodies, voices, and softness a modern hymn of reclamation shaped by the same spirit that moved for colored girls, performed by legends like Loretta Devine, Alfre Woodard, and reimagined in Tyler Perry’s 2010 film adaptation. It is both homage and evolution a reminder that our stories, our songs, and our shine are still ours to reclaim.

Reclaiming Your Song: My Response to Ntozake Shange

When I first encountered Ntozake Shange’s “Somebody Almost Walked off Wid Alla My Stuff,” I was a young married mother. I heard it from Loretta Divine in Tyler Perry’s movie For Colored Girls. It wouldn’t be for nearly 15 years later that I would revisit it in the throes of coparenting as a divorced single parent. With a different perspective of life, I wanted to remake it. As a reminder that our bodies, our brilliance, and our softness belong to us, even when the world tries to take them.

The Birth of a Movement: Ntozake Shange and the Choreopoem

In 1976, playwright and poet Ntozake Shange forever altered the landscape of American theater with her groundbreaking choreopoem, for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf.

The work emerged in a time when Black women’s voices were often erased or overshadowed, even within the civil rights and feminist movements. Shange created something the stage had never truly seen — a world where Black women could speak for themselves, about themselves, and to each other.

The term “choreopoem,” which Shange herself coined, described a new art form that defied traditional theater. It fused poetry, dance, music, and movement into one fluid language — one that lived both on the page and in the body. It wasn’t meant to be read silently. It was meant to be felt, heard, and embodied. Each woman’s voice became a note in a larger, communal symphony of survival.

Originally workshopped in small women’s spaces and community theaters, for colored girls traveled from California to New York, debuting Off-Broadway at the Public Theater before transferring to Broadway in 1976. It went on to earn Obie and Tony Award nominations, and became a cultural touchstone that shaped generations of Black feminist thought.

Through this tapestry of 20 interconnected poems, Shange gave voice to the lived experiences of Black women; our heartbreaks, our triumphs, our survival, and our sacred joy. She wrote about love and loss, about sexual violence and sisterhood, about rage and rebirth. Her words offered both witness and warning, that even when the world forgets us, we must not forget ourselves.

Among the most iconic pieces in the choreopoem is “Somebody Almost Walked off Wid Alla My Stuff.”

It’s not simply a monologue; it’s a spiritual confrontation. The speaker recognizes that something, or someone, has taken parts of her: her laughter, her rhythm, her shine. But she also recognizes her own power to reclaim them.

At its core, the poem is a cry against erasure of identity, of voice, of self. Shange’s speaker refuses to let anyone “walk off wid” her essence. What’s at stake isn’t just personal property, but something far more intimate: the right to exist fully in one’s body and being.

It is, ultimately, a reclaiming of power, and the power to name oneself, to own one’s softness, to speak one’s truth without apology. And that reclamation continues to echo today, in every woman who finds herself rising, remembering, and taking her stuff back.

Other Versions

Over the decades, Shange’s words have been carried forward by some of the most extraordinary Black actresses of our time.

Alfre Woodard’s rendition of “Somebody Almost Walked off Wid Alla My Stuff” pulses with defiance and grace, but it’s the grace that softens her fury, the defiance that lives in quiet spaces. In a PBS-filmed stage version of for colored girls, Woodard doesn’t bring thunder; she brings trembling, internal light. Her voice carries self-doubt, hesitation, yet also that unshakable core of truth. Where others may belt the poem’s anger, Woodard lets it settle into the bones, the throat, the mirror. You see the fight over what’s been taken, not just physical things, but laughter, skin, shine, even in moments of stillness.

Loretta Devine has given one of the most tender and resonant renditions of Somebody Almost Walked off Wid Alla My Stuff, not in the original 1976 stage ensemble, but in the 2010 For Colored Girls film adaptation (directed and produced by Tyler Perry), Her performance infuses the monologue with warmth, humor, and spiritual weight, demonstrating how Shange’s words continue to live and evolve across mediums and generations.

Each performance becomes a ritual of return, returning to self, to softness, to sovereignty. Every woman who speaks this piece reclaims a part of her own story.

Writing My Response: “Somebody Almost Stole My Song”

My spoken word poem, “Somebody Almost Stole My Song,” was born from the echo of Shange’s legacy, but it carries the rhythm of today.

It honors the women who’ve been touched without permission, spoken over, or stripped of their softness and still choose to reclaim it. It’s for every woman who’s been told her light was too much, her laughter too loud, her love too heavy, and still decides to shine anyway.

This poem is about reclaiming the body, the brilliance, and the breath that the world and former lovers once tried to steal. It’s about remembering that our softness is not a weakness, but rather a power in its most divine form.

The Poem: Somebody Almost Stole My Song

(A spoken word poem by Adonica Shaw, inspired by Ntozake Shange)

Somebody almost stole my skin

slipped slick fingers ‘cross my softness

and didn’t even send a sorry

no note saying “my bad, my mistake, my mercy”

just gone.

like my laughter was loose change left on a counter.

Hey!

Where you goin’ with all my shine?

my sugar-slick sway?

This is a woman’s walk

And I need my hips for Hallelujahs

my hands for holy things

My hums for healing.

Somebody almost swallowed my song,

And I ain’t bring nothin’

but the bend and the breath of it,

the beat of my blood

the soft thunder between my thighs.

You can’t have that.

You can’t hold that.

This is mine.

marvelous, messy, made-of-me…mineeeeeee

I see you hidin’ my heat,

tuckin’ my tenderness in your teeth

Like you earned it.

But I remember

how I sit with sunlight kissin’ the curve of me

How I give glory in my own skin.

You can’t have me

‘til I give me.

And I don’t give easy

Who told you you could take me?

leave me with your silence and a shadow of myself?

I want my whispers back,

my wit, my wicked, my wild.

I want my stretch marks and my stillness,

my stumbles and my shine.

I want the woman I was

before the world took a bite.

It wasn’t a spirit that stole my stuff,

It was a man with a mirror and no reflection,

a mouth that mistook my name for mercy,

a body that broke boundaries and called it, love.

But I’m callin’ it back now.

every syllable. every scar. every sacred sound.

You hear me?

This is mine.

my skin. My song. My story.

And you don’t even know

You still got it tucked under your tongue

But I do.

And I’m takin’ it back.

all my breath.

all my black.

all my brilliance.

Somebody almost stole my skin

But I caught her in the mirror

And she caught me right back.

Why This Matters To Me

When I think of Ntozake Shange, I think of a lineage of women who refuse to be written out of their own stories. This piece is for them.

For the women reclaiming their softness. For the girls growing into their power.

For the voices that refuse to be silenced again.

Because somebody almost stole our songs, but we remembered the melody.

About the Author

Adonica Shaw is a writer, doula, and student midwife whose work explores womanhood, resilience, and reclamation. She blends the rhythm of spoken word with the intimacy of lived experience to create art that heals and honors the body as both sacred and political space.

Follow her work at www.adonicashaw.com.